How I Review Outersloth Pitches

The title should be apt enough and I don’t really want to write an abstract of what you’ll see below, but this will be split into 4-ish sections:

- Pitch Deck

- Public Knowledge/Due Diligence

- Demo

- Personal Preference

But you should note my caveats, once again provided in a handy list:

- Personal! This is only and exactly how I look at pitches. I’ll make references to how I think other people act but there’s a lot of reviewers out there. (Victoria’s editor note: I would say it’s about 75% accurate to how I look at pitches.)

- Experiences and musings, not gospel. Don’t over-index on the things below. Even at Outersloth, other reviewers will influence the scales dramatically. To be honest, I’ll probably change my mind about something by the time I’ve finished writing this.

- Massively vibes-driven. There’s almost no part of the process that isn’t subject to: “I don’t know, this just feels right/wrong” as a make or break part of the deal. This part can’t be explained, but I’ll try my best.

- I really like lists. See here, but also below you’ll find that my thoughts dissolve into a pile of unsorted, loosely related bullets.

- I’m uninterested in having my mind changed. This is a kind of venting that I think provokes thought and/or conversation, but I made Outersloth specifically so we could do things our own way, for better or worse.

There will be hints and reminders as we go along, but honestly I’m winging this and wanna start writing real thoughts. The idea is that if I dump enough of my review process into the public, it’ll somehow replace part of the individual feedback I can’t provide to the hundreds of developers who submit to Outersloth.

We can’t sign everyone, but hopefully the insight helps someone gets signed somewhere.

Parts of the Pitch

I’m not good about keeping my terminology straight, but strictly speaking a pitch is built from a deck, a demo, and public knowledge (read: clout). Often I’ll refer to a deck as “the pitch” because in my opinion it’s the only thing you can count on. You might not have a demo and the reviewers might not play it. Unless you’re rather successful, you probably won’t have much clout and even so, the reviewer may not know of you. Because of this I go really hard on the deck and kinda skim over other stuff.

The Deck

Decks are the bread and butter of the pitch. If I were making a pitch, I would assume it’s the only thing people are going to look at. It needs to be absolutely bulletproof. Unfortunately with something so all-encompassing, how it looks and feels will depend a lot on what you’re selling. But I’ll shout out some key points and where I’ve seen people go wrong.

Across the whole deck, I’ll look for:

- Hooks: Is the gameplay, art, story, etc grabbing me?

- Honesty: I want to feel confident in the game and the devs. Some pitches are unbelievable.

- At best, we will have further questions if the scope, budget, timeline, teamsize, etc. don’t make sense to us. If it seems altogether outlandish you might just be rejected.

Gameplay

Well, there’s a few genres out there, so I’m not really sure what to say for all of them. But generally I want to know how the game will flow before I play it. I think the real danger of writing this section is that it needs an explanation of how I view game design as a whole to really come together, but that’s definitely a different article.

Here’s what I look for:

- Clear depiction of mechanical elements: What does the player do in a moment, a session, a playthrough.

- A content source: Something that actually keeps players playing.

- Novelties (good): What separates your game from all the others?

- Novelties (bad): These will wear out or become tedious.

- Friction: Why are players going to stop playing your game?

And here are my personal preferences and notes:

- Game state diagrams are actually pretty great. If player digs hole, gathers resources, brings to base, buys upgrades, digs bigger hole; that’s a solid loop. Expand into why the hole and/or resources are important, show parallel or recursive loops to break down layers of complexity. I have found that I usually only want one page of diagrams though. If I have to flip between pages to piece diagrams together, then it’s not abstract enough.

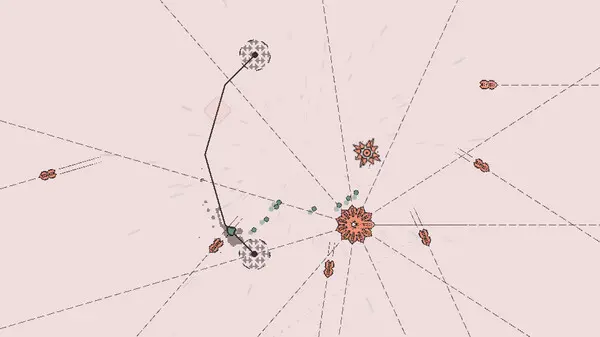

- “Actiony” gifs are ideal. This starts to get into art, but showing how key moments are started and play out is pretty good. Heavily cut animations look better, but honestly, I think I’d prefer to see raw sequences including any UI. If you make it look cool here and it’s not when I get to the demo, it’ll be a problem.

- “Actiony” in quotes because for non-action genres, you’re really looking for “quintessential” or most “impactful”. The “action” of a visual novel is the moment that makes you sit forward and continue reading.

- Trailers are also great, but:

- Remember that reviewers aren’t really buying your game and you should be even hookier. Get to the gameplay super fast, don’t use a cinematic trailer.

- Including a video will make your deck load really slow. Better to upload a private youtube vid and link/embed it.

- Personally, I wouldn’t narrate the gameplay. If it doesn’t explain itself, that’s kind of a problem and I don’t really want someone to read the deck to me. If it’s so complicated you need narration, then maybe just don’t use a video at all.

I want to add more notes because gameplay is the defining characteristic of games as opposed to books and movies, but there’s just too much. To this point, perhaps just realize that reviewers are kind of expected to be experts in all genres of games, which is insane and impossible. So your job is really to get someone with no expertise as excited as possible.

For example, I don’t understand what makes people excited about fighting games. It feels there’s no mechanical innovation in fighting games, just retheming. Will your pitch get me excited about your fighting game, even before I get to a build?

Art

This is the number one most subjective thing, so additional caveat that I like what I like and a lot of these are knee-jerk reactions that I find exceptions to often. I want enough of a sample to settle into the idea of an art style. I always do my best to get past immediate reactions and look for broader marketability vibes.

What I look for:

- Quality: What will the game look like at launch?

- Cohesive: Can they make a whole game look like this? Both in style and quality?

- Stylish: Does this art follow any well-known art styles (perhaps too closely?) or is it unique? Are the colors drab or garish or are they pleasantly punchy?

- Thoughtful: Why does your game look the way it does? Does this make sense? Does it fit?

- Effective/clear: Can I tell what’s going on from a screenshot or gif?

- Tangible: Screenshots, gifs, trailers (gameplay primarily)

Here are my preferences and notes:

- First mistake: Not making the deck look nice? Like some people are out here with text and screenshots on a blank white slide. It feels careless. More tangibly, will you not be able to create marketing materials?

- I really appreciate when the art style of the deck matches the in-game art. It’s my number one pet peeve when the pitch has a lovely art style (often illustrative or cel-shaded) and includes screenshots of the game with a totally different art style (often pixel art or physically shaded 3D). This comes from a place where Steam pages have lovely promo art and mediocre in-game art. As a consumer, I don’t want final products to do that, so as a reviewer, I don’t want pitches to do that.

- This can start to get into demos, but I honestly believe there should be some amount of final quality art in a deck. I don’t really want to download and start a demo to get that. I just want to see what you’re promising me. There doesn’t have to be a lot of it, but it should be there.

- Concepts are great, you can throw a page of those in there to show you’ve got enough ideas to fill a world. But they don’t sell the real vision of the game.

- Screenshots are great. Again they save me time from booting up the demo. But make sure they’re final quality art. Because if they’re mediocre, I’m gonna think your game is mediocre.

- Alternatively, if there’s very obvious greyboxing, that gets a pass. Just show what the greyboxes should actually look like. If you have enough final quality art then I’ll assume concepts will meet that final quality later.

- I’ll admit while writing this article, I realized that I often don’t like pixel art because it’s more likely to look generic. The constraints limit the amount of style so much that you have to be incredibly skilled to convey anything more than their SNES ancestors did. Still… art doesn’t have to be novel as long as it’s effective in other ways.

- To be honest, a lot of art quality and cohesion comes down to color for me. Like if you present gold and black deco-style key art in your pitch and your game is a grey-brown low-poly dungeon crawler, that feels misleading. Just using a cel-shader to produce gold lines along edges might be enough to pull the styles together even if the forms don’t otherwise speak to art deco. It is highly likely an artist would disagree and still be annoyed. To be honest, I probably would be too. I just want to see more colorful and stylish pitches.

Narrative

Listen. I’mma be real with you. I think narrative is the single hardest thing to sell. I can’t tell whether that’s inherent or whether I’m bad at judging it, but I think it’s really hard. It feels likely that a reviewer or publisher that specializes in narrative games would have a different view or mindset.

Here’s what I look for:

- Major character profiles: Who is in the world, who am I?

- Big plot points: Why are we even playing?

Here are my personal preferences and thoughts:

- More than anything, I feel like people tend to not include enough story in their deck. Particularly RPGs tend to gloss over it a bit, which is weird? I actually would like to know the cast of characters and the big plot points of their adventure, but we often have to ask for that later if we like the vibe and gameplay enough to bother.

- That said, big blocks of text are so hard to read. I’d say never have more than half the screen in text. Less if possible.

- Bite-sized slides that introduce key narrative points like a character or setting should typically come after you’ve hooked us with compelling gameplay.

- This touches on demos, but sample narrative should have final quality writing. Honestly, always. I can forgive a typo or out of character line here and there, but I’ve seen too many games (typically action-heavy ones) have really poor quality writing. And like everything else, if I have no final quality writing, then how do I know what it’ll be like in the end?

- There are definitely genres that get a pass. Arcade-style games almost always get a pass. That said, nothing is better than hearing: “X game had no right to have writing this good.”

- I haven’t seen a lot of these, but I really dislike lore-heavy decks. I should be clear that lore is like backstory or worldbuilding as opposed to plot outlines or character profiles. I have a few reasons for this:

- If you aren’t going to point-blank tell the player your lore, why are you telling me? Lore is for you to make a cohesive universe I will want play in. I have no use for it before it has a game and characters attached.

- I’ve never seen a lore-heavy deck in a narrative game. It’s always worldbuilding for a gritty mechanical genre. The mechanics are then usually glossed over or generic feeling.

- Reading and comprehending lots of new terms and deciding why they matter is hard.

Music and Sound

Except for rhythm games, it’s pretty uncommon to have music in a deck and nearly as uncommon for it to be final in a demo. Honestly it’s a shame because sound adds so much to games, but it’s still thought about rather late in the process.

Sound is also interestingly high-risk, high-reward. That is, if it’s bad, it will hurt you tremendously, but if it’s great, it will help you tremendously.

- For a rhythm-game, this risk-reward is doubled and unfortunately highly subjective. The music needs to be really good to the listener. As with art and writing, you effectively need final music.

- For other games, you at least need to not annoy the listener. Don’t leave super repetitive, shrill, or otherwise distasteful sounds in.

- On occasion I’ve seen pitches that include artists on Spotify or Soundcloud. Of course be sure they’re willing to work with you before you include that.

- I’ve never heard a mood playlist before, but I’d be into it.

But honestly because it’s overlooked so often, it’s hard to come up with many thoughts about sound.

Production/Budget

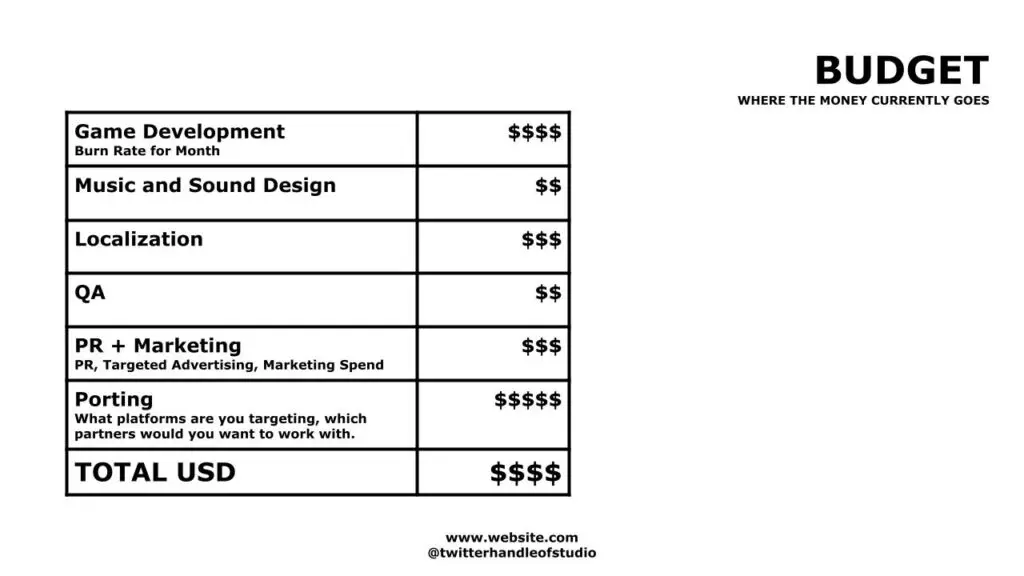

With the business stuff, generally we’re just trying to find issues and doubts as early as possible. There’s a lot of nuance to convincing people what you’re doing is reasonable.

What I look for:

- A production timeline: Broken down into milestones, not just alpha, beta, release.

- A budget: Broken down into at least departments, but headcounts over time are preferred.

Here are my preferences and notes:

- I mean… this should go without saying, but make sure you have time to make the game?

- Like… life-events tend to happen. You should have time for those.

- Please don’t work 7 days a week?

- Break the production schedule down enough that we can see the systems and believe that regular humans could complete them in the time you suggest.

- Make sure you have time/budget for QA.

- Start it early, like at feature-complete, even if just one part-time person.

- We hate to see you adding content in the launch month. Please stabilize your game before any launch.

- If you are shipping on consoles, this isn’t negotiable. You need time and/or money for cert.

- Make sure you have time/budget for localization.

- English games get a small pass here because it’s so common, but for most (non-narrative?) games the return on investment is pretty good.

- It’s pretty uncommon, but it’s cool to see demos and marketing events on the production timeline. They should be treated as smaller launches because you need to stabilize your game to present it well.

- Outersloth needs to see some budget for marketing, porting, etc. because we don’t offer those services. Full service publishers wouldn’t expect you to know this or perhaps even want to see it in your pitch.

- On one hand, we’re used to not seeing those budgets in pitches, so we’re okay asking for them around the time of signing.

- On the other, seeing services in the budget helps show us you’re thinking about it.

Market Research

I have mixed feelings about this one. I guess if I have to decide, it’s better that you add it than not, but… often it’s so bad and misguided that I just skip it. For me, it’s fine because I don’t trust anyone’s market research, but I can’t really say if someone else would hold it against you.

Honestly, I think this part also needs a separate blog, but here’s generally what I look for:

- An understanding of your genre(s) and games similar to yours

- 1-2 comparable games that were unsuccessful and rationale to your differences.

- 2-3 comparable games that are reasonably successful and rationale to your similarity.

- 1-2 comparable games as an upper bound for your success. Avoid outliers.

- Numerical estimates of your success with supporting rationale.

I feel bad already trying to write this because I think it’s going to be harsh and slightly petty, but here’s my preferences and notes:

- Every time you pick a game for your market comparisons, deeply and strongly consider: Do I want someone to compare my game to this game.

- Another point so important it gets sub-bullets.

- If you compare your game to Baldur’s Gate 3, you are doing it wrong. You don’t want to be compared to Baldur’s Gate 3.

- If you compare your game to League of Legends, you are doing it wrong. You don’t want to be compared to League of Legends.

- Two isn’t a trend, but I feel like you get where I’m going with this. Don’t use outliers in your data, you don’t have their resources and whatever you’re doing won’t stand up. Those shenanigans are for peddling NFTs to VCs.

- It’s just very frustrating to see a game say, “I will be successful” and then portray nothing of the qualities of other games.

- To be honest, this part sucks. And to be doubly honest, you shouldn’t have to do it. I wholly support you not including this in your pitch. It’s the publisher’s job to reduce your game to a range of numbers indicating whether they should or shouldn’t sign you.

- That said, if you do this work for yourself, it might indicate why you are/aren’t getting signed and be a good reason to self-publish or pick a new pitch. I recommend some understanding of the market you are trying to enter.

- Those little 2d graphs attempting to spatially relate mechanics to games are so funny I don’t mind them at all.

Team

Okay, I purposefully put this at the end of the deck section because I honestly believe that’s where it belongs. I love getting excited about a team, but the team is never the primary reason I sign a game. While every part of a pitch is a dealbreaker, I try to evaluate decks in order:

- Is the game good?

- Can it be made?

- Are the people good?

As it happens, this is also increasing order of difficulty and time-consumption to evaluate. If monkey-brain neurons don’t activate, I don’t have to worry about viability. If business-brain neurons don’t activate, I don’t have to worry about the team quality. But if everything checks out, I’ll look for:

- How many people are on your team?

- Does the team have diverse and interesting perspectives?

- Are there individual or team accolades in or out of games?

- Have you worked together before?

- If it’s not a new team, does the team have a good history of shipping games?

- Is anyone on the team a shitty person?

To be honest, I don’t have many thoughts about this. Evaluating people is pretty hard. Also the next section touches on some of this, but specifically parts outside of the deck. Mostly, just be good people?

Regardless of what you have in your deck about your team, we always do a video meeting before signing someone to shake the vibes out.

I always want to have some sense of what you’ll do if you are or are not successful. Outersloth values people who contribute to the games industry beyond simply making a game. So many games won’t be successful, so maybe take a second to consider a legacy outside the game. And if you do make a successful game, doubly consider your contributions to the industry. People will be watching.

Public Knowledge/Due Diligence

If the above things are good, I’ll usually start digging for things outside of the pitch. Most of our existing signees are generally very present and active in the industry, even if not already successful in some way. That’s really good for me because Outersloth also factors in the human qualities of developers. Not just the technical or business qualities.

Lemme break out into examples:

- Outerloop (Project Dosa) is one of the easiest examples because their CEO Eka is incredibly present in the industry. A veteran, so-to-speak. His presence makes it easy to learn about Outerloop’s track record with publishers, network size with platforms/partners, goals as a studio, history of sharing successes and wisdom, and so much more.

The quality of Outerloop as a group and Eka as its leader was really important for mitigating the risk of their large project. When there are deals that could boost their game, I can trust Eka to know about and negotiate for them.

- Midnight Munchies appeared to be a first-game studio because their pitch focused on One Button Bosses (good) and biases in the way we view game-jam-sized games and companies vs individuals. But actually, we met first at GDC because they were presenting one of their other games for awards. I don’t care much about awards, but it was the moment that showed me their history (and ideally future) of making unique and well-designed games.

- We were friends with Visai before they pitched us, but we actually gave them a soft no pending concerns with the scope of their game. I have to dodge spoilers, but it’s a pretty big leap and they didn’t have much material supporting they could pull it off.

I really hope to share more details someday, but their response was to spend a couple months specifically and thoroughly addressing our concerns. Don’t tell them this, but we were clamoring to sign their game not just because the game showed so much promise, but because they were able to focus and react so aptly to the risks we presented.

This is serendipitous stuff, but you can still facilitate this process by being open and genuine in the industry and including links to your websites and dev profiles. I think it would be disingenuous to include resumes or biographies in pitch decks. It would also be concerning if you have no presence in the industry. It may be that you’re new to the industry, which is an acceptable risk in some cases. But it may be that you appear detached from the industry, which unfortunately gives the vibe of a passerby as opposed to someone who will stay and enrich the industry.

It’s also important to note that Outerloop is our biggest budget game while Midnight Munchies is one of our smallest. The amount of rigor we judged them on is proportional to their ask. If you ask for a million dollars or more, we have to question: Are you qualified to handle that kind of money? Are you qualified to run a team that burns that kind of money? As the scale grows, the lessons for those qualifications can only be bought with time.

Demo

Personally, I avoid playing demos for as long as possible. Of the currently 9 games at Outersloth, 5 had demos. They all got signed, but only one of them got signed specifically because of the demo. All others sold me on the vision via their pitch and “extras”. To be honest, there’s one I still haven’t played.

I think this differs significantly from full-service publishers which so often require a demo (and have full-time scout staff), so I sure hope they actually play it. But in my position, demos are a trap.

- If the demo is really good, most likely I’ve already concluded that before now and I’m playing mostly for pleasure when I should probably be working.

- If the demo is really bad, most likely I’ve already known that and I’m just wasting time confirming it.

- With most demos you have to play 15+ minutes to figure out what it really is. If we have 100 submissions (we have way more), that means 25+ hours of demos.

Ultimately, I will play a demo before I seriously consider signing or anytime I need to understand the mechanical feel of a game. For me, a demo is about raw and rapid conveyance of mechanics and gamefeel. It’s so hard to make a good demo and it’s too nuanced to cover completely so here are the preferences and thoughts:

- After writing some bullets, I realized all other bullets are just rehashing this sentiment: Think deeply about what makes your game unique and what the best parts are. Show those parts as quickly and clearly as possible. Put the parts you skip by doing this somewhere else so they can be consumed at-will.

- Demos vary pretty drastically based on development cycle. If you’re asking for full development funds, I’m more likely to forgive any art and sound issues if I immediately understand why the game will be fun or interesting. If you’re asking for finishing funds, I know it would be costly to fix art or sound issues when you should be finishing with the assets you have.

- Good demo design varies widely by genre. If you’re making a narrative game, I wanna see quality writing samples. A strategy game might throw me into a set of containerized scenarios. Platformers ideally show me unique and excellent movement, abilities, etc.

- In my opinion, the demo needs to be significantly more hooky than the final product. Wow me so I can see what your best is. Don’t waste time on other things.

- This part is so important that it gets sub-bullets.

- Lots of games include unpolished fluff which distract from the best parts. It’s better to have obviously bad things next to obviously great things than have to explain specifically the quality of each element.

- For example, it’s better to have no sounds than bad sounds. It’s better to have untextured, low-poly models than off-style stock models.

- The huge caveat to this is that you have to make up for every incorrect element somewhere else. Concept arts and comparisons in the deck fill in the blanks for your grayboxes. A sample final render or sound will go long way to extrapolating what the game should ultimately become.

- For example, if you have excellent combat, but only one kind of enemy, it would behoove you to describe a few more planned enemies.

- That said, I happily accept extra notes about demos. I strongly prefer this over in-game tutorials, because tutorialization is hard and often slows the demo down. I think of notes as an agenda for a meeting that will help me stay focused. And I think this can help you too. If your notes are very long, is it because there’s many issues or lack of focus on what matters?

- In most cases I’d rather see a tech demo or debug demo that breaks down and points out specific mechanics and features. I have already been sold on the vision if I start your demo, so I want to see that it meets my expectations and you can deliver it at quality.

- Tech demos that demonstrate a particularly difficult piece of tech can be particularly valuable, like translating stylized 2D concepts into a 3D world.

A special note that complete vertical slices are great, but I find them pretty hard to justify. That’s a lot of demo that most people aren’t going to play and don’t really need to accurately judge your game. And as above, I’d expect it all to be pretty good quality unless you have other factors lifting it up. It just speaks to the risking all your eggs in one basket when honestly publishers don’t deserve (or even need) that.

Personal Preference

Ahhh, I don’t know. Maybe I shouldn’t write this part, but obviously I’m leaving it here, so take this part with the biggest grain of salt:

Lots of people ask us what kind of games we’d like/dislike to see. And there are technically answers to this, but we never give them (with the exception of ethical or pragmatic exclusions) because the opportunity cost is missing out on the game that changes our mind about the genre.

That said, you can adjust your pitch to be more appealing based on market research. I hope you read this next sentence because I don’t mean it how you might think. Instead of picking games or genres to target because they appear to have money in them, adjust a game or genre to find voids, niches, or mash-ups.

Caveat: Outersloth doesn’t need to make money to ensure we get paid because Innersloth pays our wages. So unlike dedicated publishers, we can afford to be less quantitative about what games we sign. That said, I believe everyone is just guessing at safe bets anyway, so:

- It’s easier to ship a game you’re excited about

- It’s easier to get funding for a game you can get others excited about

- If everyone is excited for your game, it’s a lot easier to sell

- “I will make you so much money” is too unreliable to get anyone genuinely excited

So even though we are less quantitative, I believe that ideas with genuine passion are still more likely to succeed.

This also starts to get into my game design philosophy (which I will write a post about later), but here’s cluster of thoughts that might help you steer your pitch towards one that excites both yourself and others. They all assume you have a game idea in mind. I can’t help you pick what interests you.

- First, find examples of other games/media that resemble your idea.

- If you are struggling, break your idea into the pitchable parts above. What media has similar art or gameplay, story, etc.

- Think hard about what parts are exciting to you. Ensure you are capturing those.

- Think even harder about which parts disappoint you. Be cruelly critical to find flaws. You can still enjoy that media despite them.

- Solve those flaws! Find other pieces of media that fix those flaws. I personally think the more outlandish the solution the better!

- Example: I don’t actually know if this is the reason, but I could imagine Crypt of the NecroDancer being a traditional roguelike that fixes the flaws of turn pacing (analysis paralysis) with beat matching from rhythm games. That’s a huge leap!

- As with the example above, you can sharpen your senses by picking apart the subtle differences between otherwise similar games. Lol, idk, I find it fun!

The beauty of this approach is that this enforces unique combinations of things (even better if you can find a novel solution instead of a chimera of existing games) and automatically points out your unique selling points. Pitch reviewers are often expected to be experts in every single game genre, but we are human and have games backlogs just as long as yours. Helping us understand your perspective against “your competitors” (games do not complete as such, but that’s yet another blog, probably) can help quite a bit.

The trick to this approach is that a pile of interesting mechanics doesn’t always make for an interesting game. It takes a lot of thought and skill to patch issues with existing genres. Particularly popular examples of games often work in the way they do for good reason, so patches may cause yet more issues. Despite any issues, I feel like it’s a pretty good exercise for sharpening your design sense.

More to the point, consider the kinds of people who like the mechanics you’re adding. Try to enter their shoes and find out why they like them! Are you mixing mechanics that hinder part of your audience? In my example above, does NecroDancer appeal more to traditional roguelike players or rhythm players? I would imagine that being forced to move on the beat might annoy turn-based traditional roguelike players. It might come as no surprise that Bard is unlocked by default for those people despite bypassing a core game feature!

Playtest Your Pitch

I think a lot about how self-similar various parts of game development are and I really think pitching could benefit from playtesting. It has all the same pros/cons as playtesting in general, but if you have even one person who will honestly tell you how they receive your pitch and honestly tell you what they like, dislike, understand, misunderstand. I think that goes a really long way.

The net result of reviewing is that you can’t be there to explain your game, so you need an all-inclusive hype-package. And reviewers won’t have time to give you feedback on your pitch, so when it doesn’t land, you’ll have nothing to improve on. But there are plenty of other people who know nothing about your pitch and will have time to give you feedback. So use that!

Conclusion

It’s still important to remember this is just my personal thought process and even then, it is incomplete and I am still learning and adapting as a reviewer. Hitting all these marks doesn’t guarantee you have the perfect pitch for Outersloth or anywhere else. But I really hope this helps give some insight into the thought process of a potential reviewer. I honestly believe that thoughtfulness and outside perspective leads to better pitches, products, so on.

With caveats out of the way, I feel like there’s so much more to say. Victoria edited out at least one spot where I complained about not having the space for a longer gameplay analysis section, so maybe that will be next. (Victoria’s editor note: Yes.) I also had “an unhinged livetweet session” while watching a GDC talk about pitch decks that I will save for another time. (Victoria’s editor note: It really was a bit too unhinged for this.) Feel free to throw things at me on social media if you’d like to me rant about it. (Victoria’s editor note: Oh no.)

I have seen dozens of great ideas marred by issues with the pitch. We don’t have the time and resources to find what the intent was or give this kind of feedback individually. But I’d still love to see everyone get to make their games, so I hope this broad feedback suffices. But until I next spend two months writing 12 pages of whatever this post has become, I hope this helps more people get their ideas through the door.

Best of luck!

Forest